Portable Sawmill Helps Scottish Teacher Prove Viability of Traditional Woodcraft

James Thomson of Glenrothes, Scotland started Thomson Timber in 2007. Previously trained as a mechanical design engineer, he had worked in Australia and Edinburgh before returning home and taking up teaching woodworking for twenty years.

“The inspiration came from my students,” James recalls. “One of the kids said to me, ‘Why are you teaching us how to do traditional carpentry, when the chances are that when we leave school, we’re all going to work in factories?’ I thought to myself that I should really try to show them where these traditional skills are still being used.”

The question was quite relevant, so James set out to discover where traditional woodworking skills are still essential in today’s industries. High-end furniture construction was one area, as well as the restoration work on the old oak framed buildings around the UK. However, the area that really caught James’ attention was the resurgence of interest for post-and-beam timber frame buildings.

James decided that building a timber frame would be a great way to illustrate the usefulness of their woodworking skills to the kids. With the involvement of local timber companies who donated the timber, James ran an extra-curricular course, and they built a timber-frame structure together with the kids.

“I was trying to encourage the kids themselves to look at other avenues of employment,” James says. “That was the whole point of it all.” However, when the building was finished, several of the sponsoring timber companies told him that there was really a market in the area for such construction, and that he should make a go at it.

In 2007, he went fulltime with Thomson Timber after building some trial buildings, which quickly sold. He found that his varied experiences with mechanical engineering, experience with desktop publishing and some marketing contributed significantly to their success. His proficiency with AutoCAD made designing buildings and standardising the traditional techniques and joinery easier and more efficient.

“My son Craig works with me fulltime. He graduated in Art and Philosophy,” James shares with a bit of a grin. “I was apprehensive as to where his career would go with an Art and Philosophy degree. Having said that, his ability to visualise things in three dimensions – you never have to tell him something twice. Plus, he taught himself AutoCAD.”

Thomson Timber is located just east of Glenrothes, Scotland. The location is rural, but within a short drive of the coast and Edinburgh. The location has proved ideal. They attend local fairs and shows, and generate a great deal of enquiries from their timber frame stand. People are naturally attracted to the stand, and as they talk over the possibilities, many of the conversations result in future work.

“People who have horses, if you can describe it that way,” James shares. “They are the people that we tend to have as clients.” The common denominator among their clients is that they own land, horses, or both. Their last show was the Blair Castle Horse Trials, near Pitlochry, Scotland, and that show resulted in more enquiries in the first day than any other show they had attended.

“If you look at what is on the market today, they [ready-made buildings] seem too flimsy,” James says. “People don’t like that flimsiness. They would rather spend the extra and have something that is going to last a lifetime.”

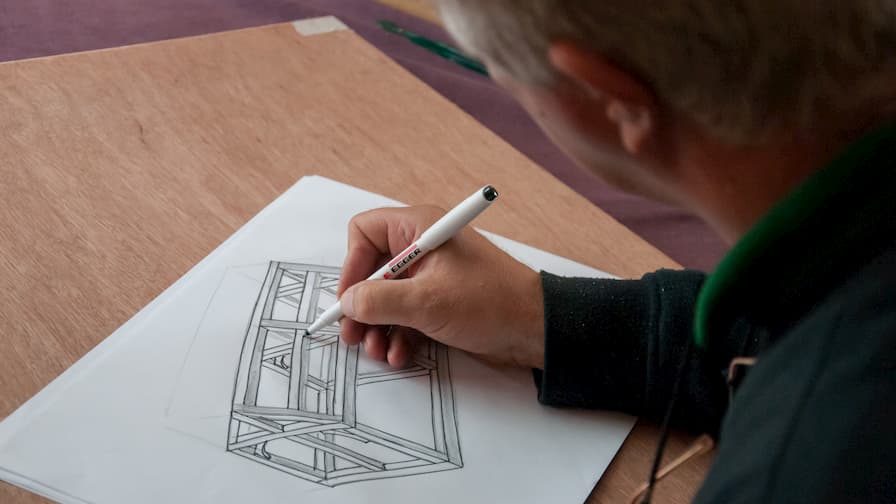

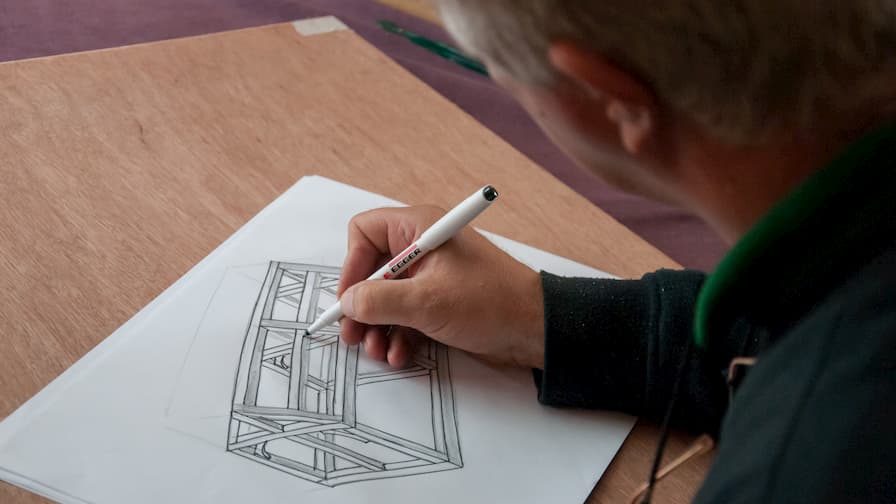

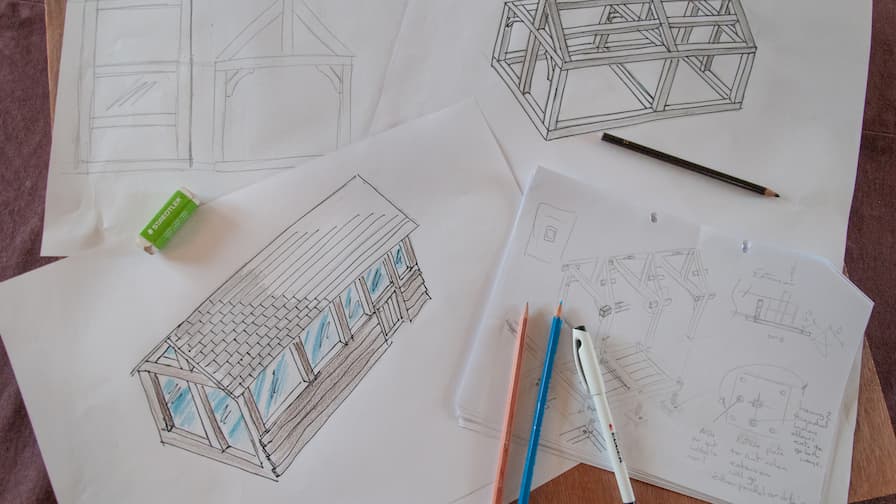

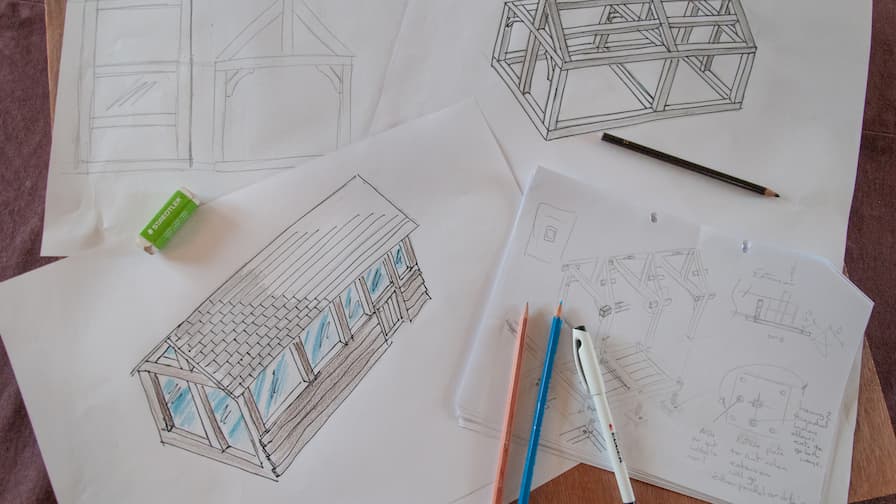

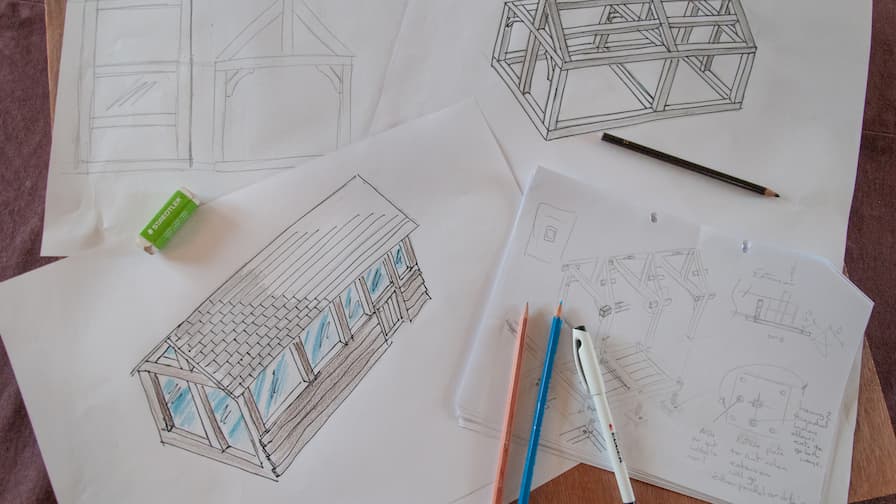

James initially sits with the client and discusses their ideas. As they talk, he sketches out a preliminary three-dimensional drawing of the house extension, barn, gazebo, or whatever else the client might be dreaming of. As he sketches, they discuss the general project parameters, making changes to the plan as needed.

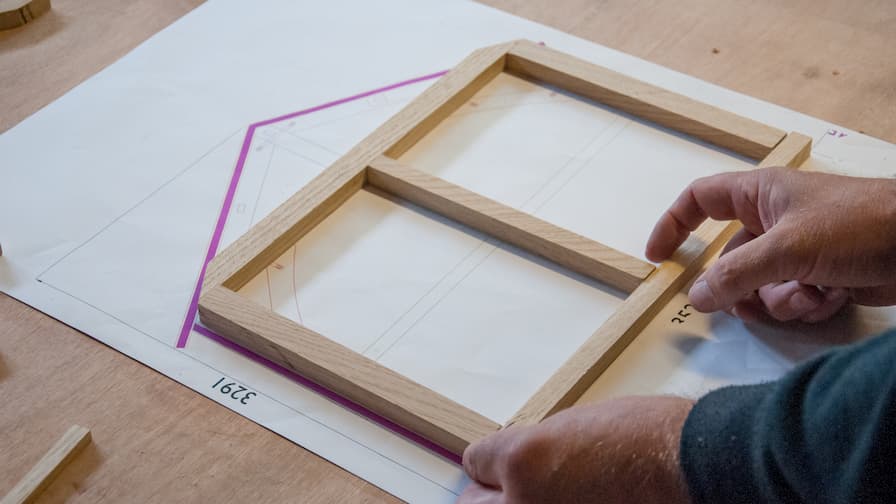

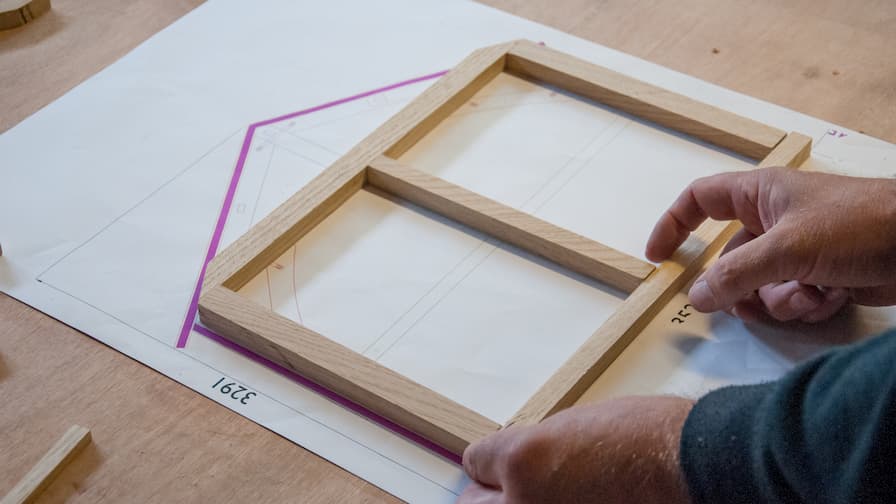

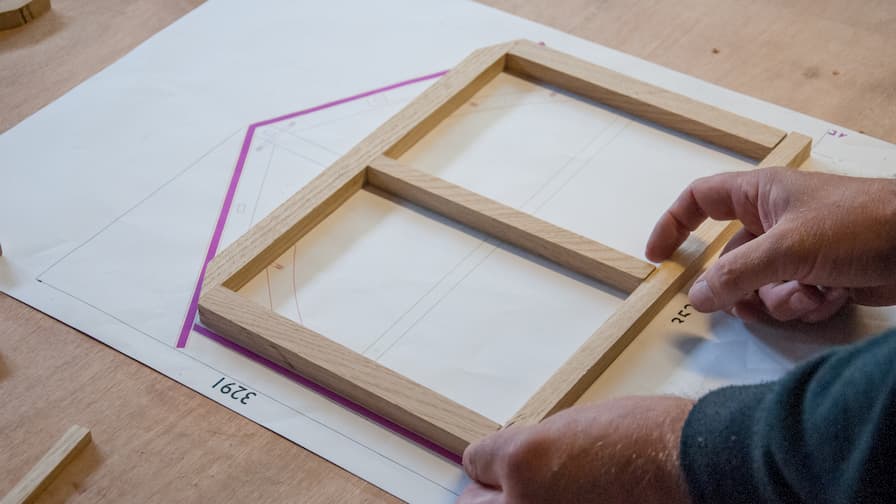

James then makes an official proposal and drawing in AutoCAD, which generates an accurate materials list and final quote for the project. When a price is agreed on, James often will then make a scale model of the project and review it one more time with the client.

“In my experience, having that hands-on approach is vital where they can take the model and move it around in space,” relates James. “They can decide to move a door, add a different kind of window, or change the orientation slightly.” Building the model helps him think through how he wants to accomplish some of the more technical joints and carpentry on the final project.

Several times, James has employed his computer skills to superimpose a photo of the model onto a photo of the client’s yard, to give them an accurate look at what the final project will look like naturally, or to make sure that the building will not obstruct their existing view out to the sea. This added effort has helped finalise more than one deal.

Once the project plan is finalised, the real work begins! Logs are often selected before they are felled, so that the right lengths and cuts are made. Once the logs are delivered, further selection takes place as they pick and choose the right logs for each component.

Then the logs are loaded onto their sawmill to be turned into beams or posts. Posts, for example, must be cut from the very centre of the tree – boxed heart, so that when they shrink in the future, they will shrink equally on all four sides.

“That’s one of the main reasons we have our own sawmill,” James explains. “We couldn’t get commercial sawmills to supply us with specific cuts from a tree. In timber framing, it’s very important. We need to know we can use certain cuts of the tree for certain areas, knowing in which ways timbers will shrink and distort.”

The LT15 is an affordable first step into high quality sawmilling for one’s own purposes. Although on the lower end as far as price-point, James’ sawmill has proved quite robust for close to 10 years, and capable of cutting diameters of up to 70cm and lengths up to 5.4 metres.

Beams and posts are milled slightly oversized, because James’ sawmill includes an additional attachment for final planing and moulding.

“The advantage of having the Wood-Mizer moulder on the same rails as the sawmill means we never have to take that timber off the machine,” James shares. “We can plane it to exactly what we want. It gives us a nice surface finish for interior timbers, and gives us an accurate and planed beam that we can easily work out reference faces for the traditional carpentry.”

Once the beam or post is square and smooth, the AutoCAD drawing is referenced and a rod used to precisely mark out the locations of the joints. These are then cut with a chain mortiser and traditional chisels.

A trial assembly of the building is generally made at Thomson Timber, whether partially or the whole project. For projects that are impractical to fully assemble, they have practice mortise and tenon joints on hand to make sure everything fits as it should.

Because of requests from customers for a building that could be dismantled easily, James has adopted and now prefers a mechanical linking system to connect his joints over the traditional mortise and tenon method.

“I came across a dozen or so different methods,” recalls James, “But in my opinion, the simplest and most efficient way of joining the timbers is to use the TimberLinx system. The whole building can be assembled virtually with only an Alan key. We can take buildings up and down in a couple of hours, without special equipment or special skills.” One of James’ goals is to leverage this system in a way that he can sell smaller buildings as a DIY kit, which certainly sounds promising as an area of business growth.

They enclose the building using insulated panels backed with plywood. The inside can be pre-painted or stained depending on the final look required by the client. The panels can be used as the roof insulation as well, allowing them to make the building wind and watertight in the same day.

Between larger projects, construction of firewood stores, furniture and fireplace mantles keeps them busy. They sell mantles all over Britain, and use a wide belt sander with a 1.2 metre width capacity to produce mantles and tabletops.

“From my point of view,” James shares, “Being able to produce items that will outlive me, and making use of the craftsmanship that’s required to achieve that, that’s probably the main attraction of my business. One of the things we find is that our customers spend a lot of time sitting in the building, just looking at the building, rather than looking out the windows! That’s a great compliment.”

James Thomson of Glenrothes, Scotland started Thomson Timber in 2007. Previously trained as a mechanical design engineer, he had worked in Australia and Edinburgh before returning home and taking up teaching woodworking for twenty years.

“The inspiration came from my students,” James recalls. “One of the kids said to me, ‘Why are you teaching us how to do traditional carpentry, when the chances are that when we leave school, we’re all going to work in factories?’ I thought to myself that I should really try to show them where these traditional skills are still being used.”

The question was quite relevant, so James set out to discover where traditional woodworking skills are still essential in today’s industries. High-end furniture construction was one area, as well as the restoration work on the old oak framed buildings around the UK. However, the area that really caught James’ attention was the resurgence of interest for post-and-beam timber frame buildings.

James decided that building a timber frame would be a great way to illustrate the usefulness of their woodworking skills to the kids. With the involvement of local timber companies who donated the timber, James ran an extra-curricular course, and they built a timber-frame structure together with the kids.

“I was trying to encourage the kids themselves to look at other avenues of employment,” James says. “That was the whole point of it all.” However, when the building was finished, several of the sponsoring timber companies told him that there was really a market in the area for such construction, and that he should make a go at it.

In 2007, he went fulltime with Thomson Timber after building some trial buildings, which quickly sold. He found that his varied experiences with mechanical engineering, experience with desktop publishing and some marketing contributed significantly to their success. His proficiency with AutoCAD made designing buildings and standardising the traditional techniques and joinery easier and more efficient.

“My son Craig works with me fulltime. He graduated in Art and Philosophy,” James shares with a bit of a grin. “I was apprehensive as to where his career would go with an Art and Philosophy degree. Having said that, his ability to visualise things in three dimensions – you never have to tell him something twice. Plus, he taught himself AutoCAD.”

Thomson Timber is located just east of Glenrothes, Scotland. The location is rural, but within a short drive of the coast and Edinburgh. The location has proved ideal. They attend local fairs and shows, and generate a great deal of enquiries from their timber frame stand. People are naturally attracted to the stand, and as they talk over the possibilities, many of the conversations result in future work.

“People who have horses, if you can describe it that way,” James shares. “They are the people that we tend to have as clients.” The common denominator among their clients is that they own land, horses, or both. Their last show was the Blair Castle Horse Trials, near Pitlochry, Scotland, and that show resulted in more enquiries in the first day than any other show they had attended.

“If you look at what is on the market today, they [ready-made buildings] seem too flimsy,” James says. “People don’t like that flimsiness. They would rather spend the extra and have something that is going to last a lifetime.”

James initially sits with the client and discusses their ideas. As they talk, he sketches out a preliminary three-dimensional drawing of the house extension, barn, gazebo, or whatever else the client might be dreaming of. As he sketches, they discuss the general project parameters, making changes to the plan as needed.

James then makes an official proposal and drawing in AutoCAD, which generates an accurate materials list and final quote for the project. When a price is agreed on, James often will then make a scale model of the project and review it one more time with the client.

“In my experience, having that hands-on approach is vital where they can take the model and move it around in space,” relates James. “They can decide to move a door, add a different kind of window, or change the orientation slightly.” Building the model helps him think through how he wants to accomplish some of the more technical joints and carpentry on the final project.

Several times, James has employed his computer skills to superimpose a photo of the model onto a photo of the client’s yard, to give them an accurate look at what the final project will look like naturally, or to make sure that the building will not obstruct their existing view out to the sea. This added effort has helped finalise more than one deal.

Once the project plan is finalised, the real work begins! Logs are often selected before they are felled, so that the right lengths and cuts are made. Once the logs are delivered, further selection takes place as they pick and choose the right logs for each component.

Then the logs are loaded onto their sawmill to be turned into beams or posts. Posts, for example, must be cut from the very centre of the tree – boxed heart, so that when they shrink in the future, they will shrink equally on all four sides.

“That’s one of the main reasons we have our own sawmill,” James explains. “We couldn’t get commercial sawmills to supply us with specific cuts from a tree. In timber framing, it’s very important. We need to know we can use certain cuts of the tree for certain areas, knowing in which ways timbers will shrink and distort.”

The LT15 is an affordable first step into high quality sawmilling for one’s own purposes. Although on the lower end as far as price-point, James’ sawmill has proved quite robust for close to 10 years, and capable of cutting diameters of up to 70cm and lengths up to 5.4 metres.

Beams and posts are milled slightly oversized, because James’ sawmill includes an additional attachment for final planing and moulding.

“The advantage of having the Wood-Mizer moulder on the same rails as the sawmill means we never have to take that timber off the machine,” James shares. “We can plane it to exactly what we want. It gives us a nice surface finish for interior timbers, and gives us an accurate and planed beam that we can easily work out reference faces for the traditional carpentry.”

Once the beam or post is square and smooth, the AutoCAD drawing is referenced and a rod used to precisely mark out the locations of the joints. These are then cut with a chain mortiser and traditional chisels.

A trial assembly of the building is generally made at Thomson Timber, whether partially or the whole project. For projects that are impractical to fully assemble, they have practice mortise and tenon joints on hand to make sure everything fits as it should.

Because of requests from customers for a building that could be dismantled easily, James has adopted and now prefers a mechanical linking system to connect his joints over the traditional mortise and tenon method.

“I came across a dozen or so different methods,” recalls James, “But in my opinion, the simplest and most efficient way of joining the timbers is to use the TimberLinx system. The whole building can be assembled virtually with only an Alan key. We can take buildings up and down in a couple of hours, without special equipment or special skills.” One of James’ goals is to leverage this system in a way that he can sell smaller buildings as a DIY kit, which certainly sounds promising as an area of business growth.